Understanding Thermal Batteries and Their Basics

Thermal batteries are specialized energy storage devices that use heat to generate electricity. They rely on principles like heat transfer, melting, and phase change to store and release energy efficiently. By understanding concepts such as specific heat, latent heat, and thermodynamics, students can grasp how these batteries work and their applications in real-world technology, from emergency power sources to space missions.

I am writing this blog to help high school students first understand the basic concepts of thermal physics—such as heat, temperature, conduction, convection, and radiation—and then see how these concepts come together in real-world applications like thermal batteries. My goal is to make complex ideas approachable, show how fundamental physics is closely linked to cutting-edge technology, and inspire curiosity about how science learned in the classroom connects to innovations shaping the future

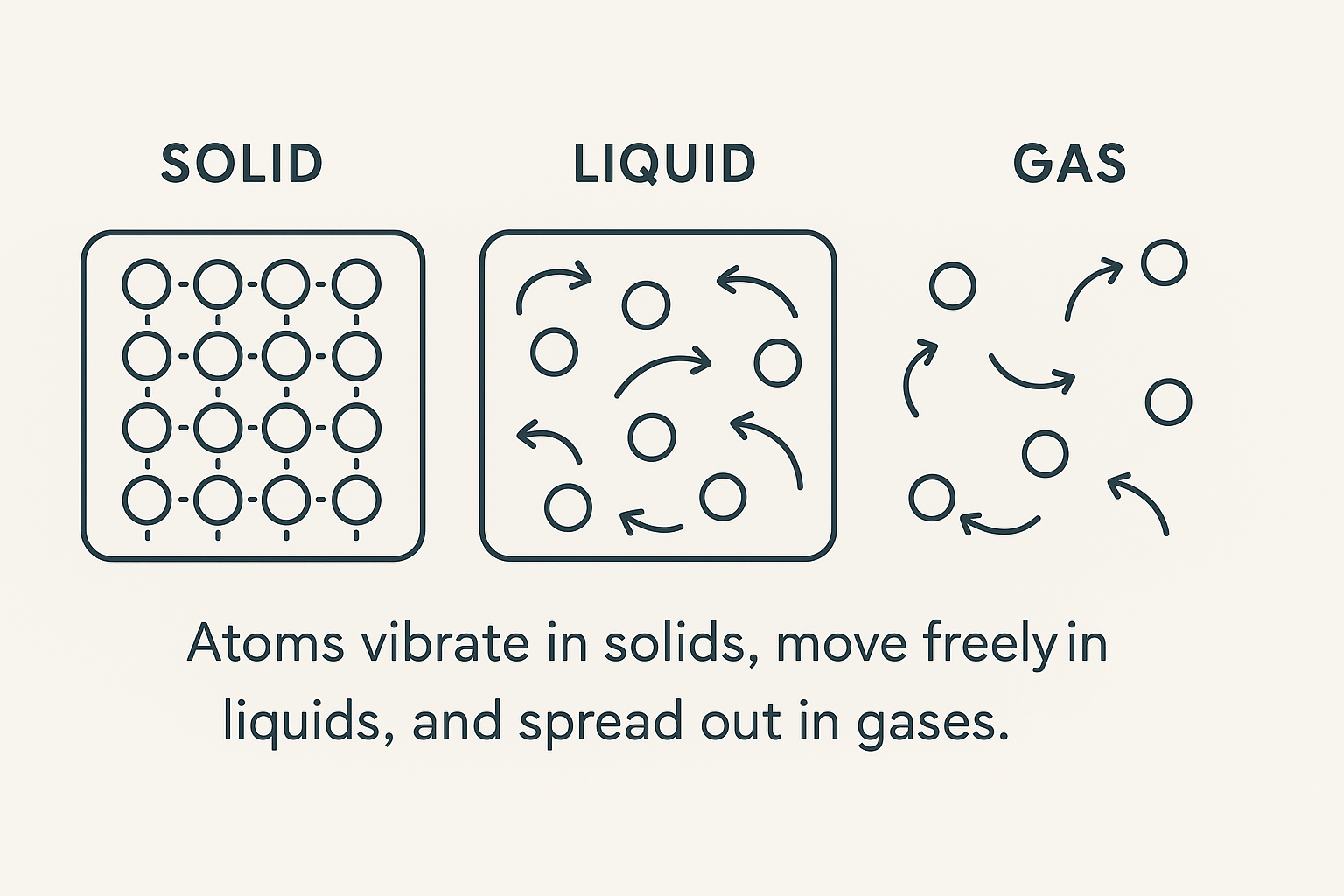

The Melting Process: How Atoms Behave

When a solid begins to melt, important changes are happening at the atomic level. In a solid, atoms or molecules are packed closely together in a fixed structure. They cannot move freely, but they constantly vibrate in place. As heat is added, these vibrations grow stronger and faster. Eventually, at the melting point, the particles have enough energy to partially break free from the bonds or forces holding them in their rigid arrangement.

During melting, the organized structure of the solid collapses into the looser arrangement of a liquid. The particles are still close together, but now they can slide past one another instead of staying locked in place. This is why liquids flow while solids keep a fixed shape. A good example is ice: in solid ice, water molecules form a rigid crystal held together by hydrogen bonds. As ice absorbs heat at 0 °C, those bonds loosen and break, allowing the molecules to move freely as liquid water.

What’s important to notice is that while a substance is melting, its temperature does not increase even though heat is still being added. This is because the energy is being used to break the bonds between particles rather than to make them move faster. This “hidden” energy used during melting is called the latent heat of fusion. Only after all of the solid has turned into liquid will the temperature begin to rise again with further heating.

Different substances melt in different ways depending on how strong their bonds are. Water, for example, requires a relatively large amount of energy to melt because of its strong hydrogen bonding. Metals often melt at much higher temperatures, since their atoms are held tightly together by metallic bonds. Substances like wax, on the other hand, melt easily at much lower temperatures, because their molecules are held together by weaker forces.

In all cases, though, the melting process tells the same story: as heat is added, atoms or molecules gain energy, vibrate more intensely, and eventually overcome the forces holding them in place. The solid loses its rigid structure, and a liquid with flowing, moving particles is formed.

Latent Heat and Specific Heat

Heat is one of the most fascinating forms of energy because it doesn’t always behave the way we expect. When you heat something, sometimes its temperature rises steadily, but at other times, the temperature stops increasing even though heat is still being added. This surprising behavior is explained by two key concepts in thermal physics: specific heat and latent heat.

Specific heat tells us how much heat energy is needed to raise the temperature of a given mass of a substance by one degree. Substances differ widely in their specific heat values—some need very little heat to warm up, while others can absorb a great deal of energy before showing much change in temperature.

Latent heat, on the other hand, explains what happens when a substance changes its state—like melting, freezing, or boiling. During these changes, heat energy is absorbed or released without affecting the temperature. Instead of making the particles move faster, this hidden energy goes into breaking or forming bonds between them.

Different materials show striking differences in their specific heat and latent heat values. Water, for example, has a very high specific heat, meaning it resists quick changes in temperature and can store large amounts of heat. This makes it crucial in regulating climates and in living systems. Metals, by contrast, have much lower specific heats, so they heat up and cool down rapidly. When it comes to latent heat, water again stands out: it takes an unusually large amount of energy to melt ice or to boil liquid water. Substances like paraffin wax or many metals require far less energy to change state, which is why they are used in thermal storage and manufacturing processes.

Differences Between Materials

Not all substances respond to heat in the same way. In fact, one of the most fascinating parts of thermal physics is how differently materials store and release energy. These differences help explain why certain materials are chosen for specific tasks in nature, industry, and technology.

Specific heat capacity varies widely across substances. Water is an outstanding example: it has one of the highest specific heat values of any common material, meaning it can absorb or release large amounts of heat with only a small change in temperature. This property makes oceans and lakes important “climate stabilizers” for Earth. Metals like copper and aluminum, on the other hand, have very low specific heat capacities. They heat up and cool down extremely quickly, which makes them excellent choices for cookware or heat exchangers where rapid heating is desirable. Materials like stone, sand, or concrete fall in between—they hold moderate amounts of heat, which is why they are often used in building construction to regulate indoor temperatures.

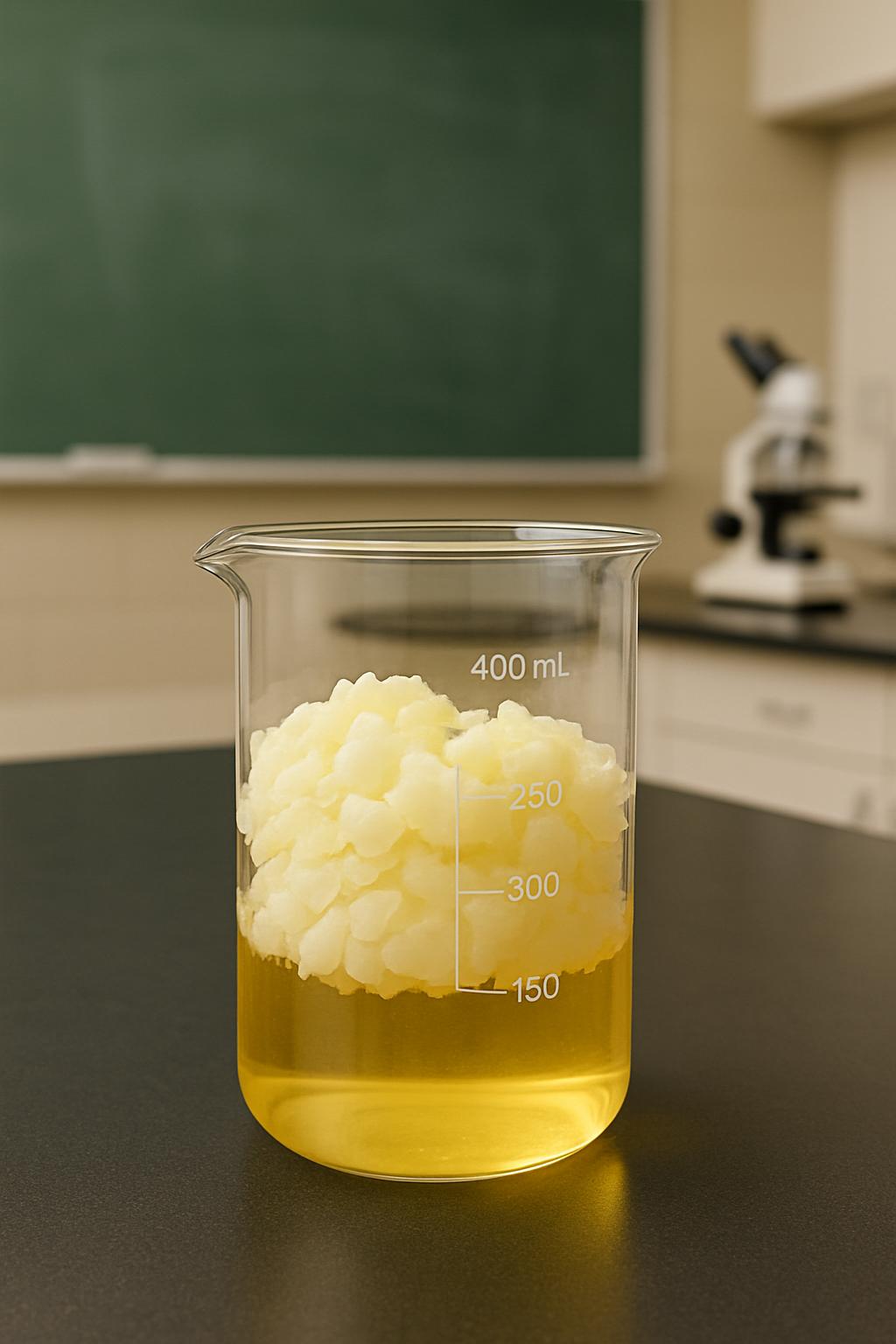

Latent heat, the energy required to change a material’s state, also shows striking differences. Water requires a large amount of energy to melt or boil, which makes ice an effective coolant and water vaporization a powerful cooling mechanism in sweating or industrial processes. Metals, in contrast, often melt with much lower latent heat values compared to water, which is one reason they are easier to reshape and mold in manufacturing. Paraffin wax is another interesting case: it melts at relatively low temperatures but stores a large amount of latent heat in the process. This unique property makes it a popular choice in thermal batteries and phase-change materials, where the goal is to store energy efficiently and release it later when needed.

These variations aren’t just academic—they directly influence design choices. For example, engineers may choose metals for applications where quick heat transfer is critical, water for systems requiring stable thermal regulation, and waxes or salts for thermal energy storage in renewable energy technologies. By comparing how different substances respond to heat, we gain insight into why materials are matched so carefully with the roles they play in science and engineering.

Thermodynamics: The First Two Laws

Thermodynamics is the branch of physics that studies how heat and energy move and change form. Two of its most important principles are the First Law of Thermodynamics and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Together, they form the foundation for understanding energy use, efficiency, and the limits of what machines and natural systems can do.

The First Law: Conservation of Energy

The First Law states that energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only be transformed from one form to another or transferred between systems. In simpler terms, the total amount of energy in the universe always remains constant.

For example, when fuel burns in an engine, the chemical energy stored in the fuel is converted into heat and mechanical work. Similarly, when you eat food, your body converts the stored chemical energy into motion and heat. The forms of energy change, but the total never disappears.

This law assures us that when we design systems, like engines or batteries, we can account for all the energy going in and out. In the case of thermal batteries, the First Law guarantees that the heat energy stored inside—whether in molten salts or waxes—is not lost, but will later reappear as useful energy when the system is discharged.

The Second Law: Entropy and Efficiency

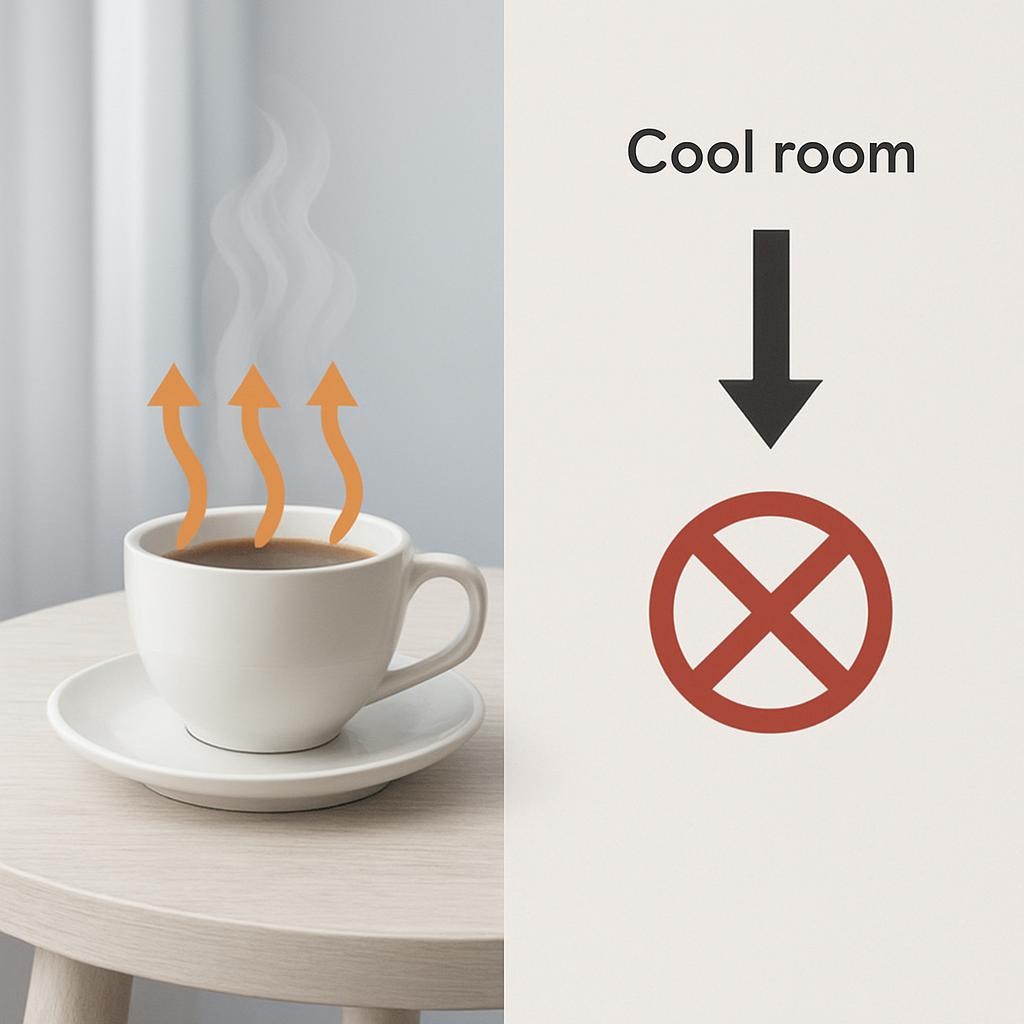

The Second Law is about the direction of energy flow and the concept of entropy, which is often described as a measure of disorder. It tells us that while energy is conserved (First Law), every time energy changes form, some of it becomes less useful—often as waste heat. In other words, energy transformations are never 100% efficient.

A classic example is a hot cup of tea cooling in a room. Heat naturally flows from the hot tea to the cooler air, but the reverse—air warming the tea without input—is impossible. This one-way flow of heat reflects the natural tendency toward greater entropy.

The Second Law sets a limit on how efficiently we can use stored energy. For thermal batteries, this means that while heat can be stored and later converted to electricity, some portion of the energy will always be lost as waste heat. Engineers work to minimize these losses, but the law reminds us that perfect efficiency is unattainable.

Thermodynamics and Thermal Batteries

Together, these two laws explain both the potential and the limits of thermal batteries. The First Law ensures that the energy stored during charging is still there when we need it. The Second Law reminds us that no matter how clever our design, we cannot extract every last bit of that energy as useful work—some will inevitably escape as heat. This balance between conservation and efficiency is why thermal physics is so crucial in designing next-generation energy storage systems.

Kinetic Molecular Theory: Energy in Molecules

The kinetic molecular theory is a model that explains how matter behaves by looking at the tiny particles (atoms and molecules) that make it up. It helps us understand temperature, heat, and why matter changes states.

The kinetic molecular theory explains the behavior of matter by focusing on the motion of its particles. It says that all matter is made up of tiny particles—atoms or molecules—that are always in motion. In solids, these particles vibrate in fixed positions; in liquids, they move more freely and slide past each other; and in gases, they move rapidly and spread far apart. The speed of these particles depends on temperature: the hotter a substance is, the faster its particles move, and the cooler it is, the slower they move. In short, temperature is a direct measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles in a substance.

Kinetic vs. Potential Energy in Matter : In any state of matter, particles have both kinetic energy and potential energy. Kinetic energy comes from the motion of the particles—whether they are vibrating in place, sliding past each other, or moving freely in all directions. Potential energy, on the other hand, is stored in the interactions and bonds between particles. In solids, particles are tightly bound, so potential energy dominates while kinetic energy is smaller. In liquids, the balance shifts, with particles moving more freely but still held together by weaker forces. In gases, particles are far apart and moving very fast, so kinetic energy is much greater while potential energy is minimal.

This balance between kinetic and potential energy determines the state (solid, liquid, or gas) of matter.

How Energy Changes with States of Matter: As matter changes state, the way energy is stored and used also changes. When a solid is heated, the added energy first increases the particles’ kinetic energy, making them vibrate faster. At the melting point, however, extra heat goes into breaking the bonds between particles, increasing their potential energy instead of temperature. In the liquid state, heating again raises the kinetic energy, causing particles to move more quickly. At the boiling point, the added heat is used to completely separate the particles, greatly increasing their potential energy while the temperature stays constant. Once in the gas state, further heating mostly increases kinetic energy, as particles move faster and collide more forcefully.

Relevance to Thermal Batteries

Thermal physics isn’t just theory—it powers innovations like thermal batteries. Thermal physics is at the heart of understanding how thermal batteries work and why they are so valuable in solving real-world energy challenges. The concepts explored on this site—like heat transfer, specific heat, latent heat, and thermodynamics—form the scientific foundation for all thermal battery technology. By learning how heat moves, is stored, and changes materials, students can see how basic physics translates directly into advanced energy storage solutions, making renewables more reliable, powering critical space missions, and helping balance energy needs day and night. Gaining a strong grasp of these topics doesn’t just help in physics class—it opens up an understanding of tomorrow’s technology and demonstrates how fundamental science enables innovation in energy and sustainability

- These batteries store energy as heat, often using materials that can melt and solidify efficiently.

- When needed, the stored thermal energy can be converted into electricity.

- The principles of latent heat, specific heat, and thermodynamics directly apply here.

This makes thermal batteries important for renewable energy systems, where we need to store solar or wind power for later use.

Thermal batteries: An introduction

Thermal batteries are devices that store and release heat to generate power. They rely on principles like melting, latent heat, and thermodynamics to function efficiently.

Understanding thermal batteries

Thermal batteries store and release heat energy for various practical uses in everyday technology and industry.

One effective way to store thermal energy is by using phase change materials (PCMs), which are substances that absorb or release a large amount of heat when they change phase (for example, from solid to liquid). PCMs are widely studied for sustainable energy solutions because they have a high thermal storage capacity and can store heat within a narrow temperature range. In other words, PCMs can hold a lot of heat without getting extremely hot themselves. This is due to latent heat – the heat energy absorbed or released during a phase change. For example, when ice melts it stays at ~0 °C until fully melted, even though heat is being added; that added heat is stored as latent heat in the phase changesolartubs.com. Thanks to this property, a PCM can absorb a huge amount of energy at an almost constant temperature (its melting point)en.wikipedia.org. This makes PCMs ideal for thermal batteries, since they can charge (store heat) and discharge (release heat) while keeping the temperature relatively stable for practical use.

Simulation Overview

We used LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) to model how a PCM-based thermal battery behaves at the microscopic level. This means we simulated atoms/molecules of a PCM and observed how the system responds as it reaches thermal equilibrium. Molecular dynamics simulations like this provide insight into PCM behavior at the atomic scale and help researchers design better thermal storage materialspubs.rsc.org.

During the simulation, we tracked several key properties of the system over time (measured in simulation steps):

Potential Energy (PotEng) – energy stored in the material’s molecular structure (lower potential energy generally means a more stable arrangement of atoms).

Kinetic Energy (KinEng) – energy of motion of the particles (directly related to temperature; faster-moving atoms = higher kinetic energy).

Total Energy (TotEng) – the sum of potential + kinetic energy (for a closed system, this should remain constant if no energy is added or lost).

Temperature – how hot the system is, measured in Kelvin (K).

Pressure – the internal pressure of the system in atmospheres (how much force the particles exert on the container walls).

Volume – the size of the simulation box (volume can change if the simulation allows expansion or contraction under pressure changes).

After an initial adjustment period (as the PCM sample settled into a stable state), the simulation produced graphs for each of these properties over time. Below, we interpret each graph and explain what it tells us about the system’s thermal stability, energy conservation, and overall behavior.

Potential Energy vs Step

The graph of potential energy (energy stored in atomic bonds and interactions) shows a rapid drop at the very beginning and then levels off, fluctuating only slightly over time.

Initially, the PCM model had a higher potential energy, but within the first few simulation steps it released that energy as it settled into a more stable structure (lower potential energy state). After this early dip, the potential energy stays roughly constant on average, with just small jittery fluctuations. These tiny ups and downs are normal and represent the atoms vibrating, but there’s no long-term rise or fall.

What it indicates: The material has reached a stable state in terms of internal energy. The PCM isn’t undergoing any more big changes or reactions; it has settled into equilibrium. This stability in potential energy suggests the structure is holding together firmly and the system is thermally stable (no continuous energy gain or loss in bonds).

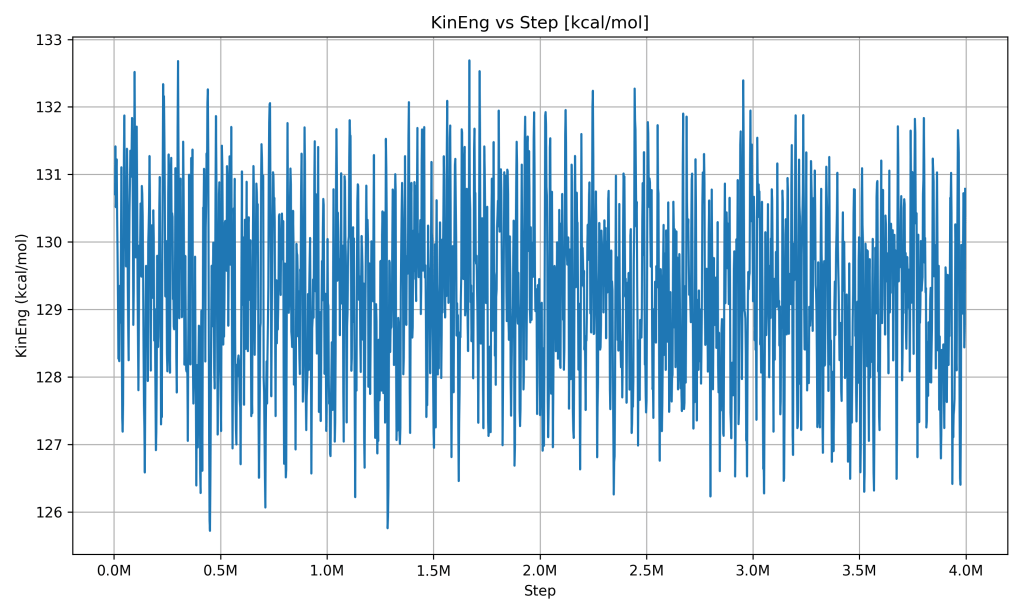

Kinetic Energy vs Step

Kinetic Energy vs Simulation Step. The kinetic energy graph (which reflects the energy of motion of the particles) mirrors the behavior of the temperature graph. After a short initial adjustment, the kinetic energy stays around a constant level with only small fluctuations. This makes sense because at a steady temperature, the average kinetic energy of the molecules should remain stable (temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of particles).

What it indicates: The molecules in the PCM kept moving at roughly the same average speed the entire time, meaning the system’s thermal state was steady. Any tiny bumps in the line are just random motion differences at each moment, but there’s no trend of kinetic energy rising or falling. This further confirms the thermal stability of the system – it’s another way of saying the temperature stayed steady. When the PCM was absorbing or releasing heat, it wasn’t causing the particles to speed up or slow down overall in any lasting way, which suggests that heat energy was managed by the phase change process (potential energy) rather than changing the temperature. The stable kinetic energy alongside stable potential energy and total energy reinforces that the simulation reached an equilibrium.

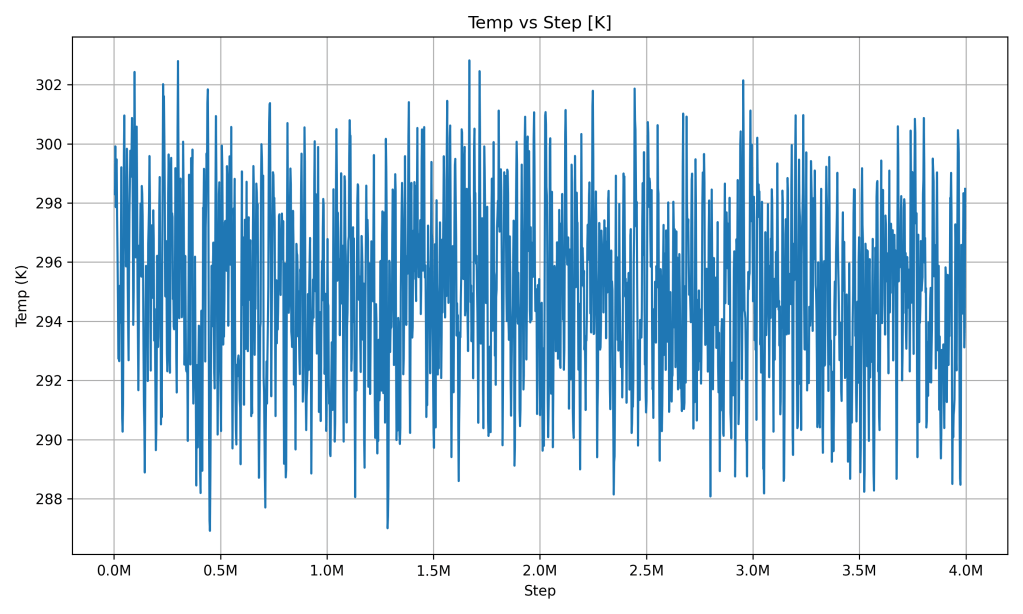

Temperature vs Step

The temperature of the system stays very close to a constant value (around 298 K, which is roughly 25 °C, about room temperature) throughout the simulation. In the graph, after a brief settling phase, the temperature line hovers around this value with only minor wiggles. Those small fluctuations (a few degrees at most) are normal random variations as atoms move, but there’s no overall increase or decrease in temperature over time.

What it indicates: The PCM maintained a stable temperature during the simulation. This reflects excellent thermal stability – the material isn’t heating up or cooling down unexpectedly. In fact, this kind of behavior is a hallmark of PCMs: they can absorb or release heat without large temperature changes (until a phase change is complete)solartubs.com. The steady temperature here suggests that if the PCM were absorbing heat, it was likely using that energy to change phase (store latent heat) rather than to get hotter. In a thermal battery context, this means the PCM can keep the output temperature steady while charging or discharging, which is very useful for delivering consistent heat.

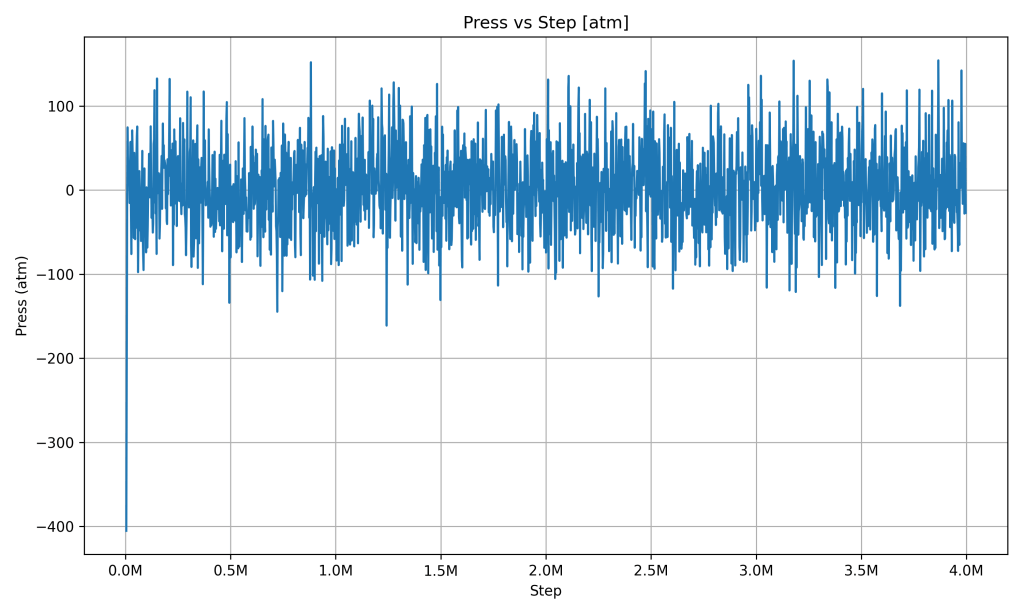

Pressure vs Step

The pressure graph has a lot of jagged spikes at first, then centers around a steady value as time goes on. Early in the simulation, pressure fluctuated dramatically – you can see big swings (even negative pressure initially, meaning the system was under tension). This happened as the PCM adjusted its volume and arrangement. Soon after, the pressure oscillates around an average value (close to 1 atm, which is atmospheric pressure) with smaller swings.

What it indicates: The system’s pressure became balanced and stable on average. Those remaining ripples in the graph are due to molecules constantly moving and bumping around (which is normal), but importantly, there’s no drift upward or downward in pressure over time. This means the PCM isn’t expanding uncontrollably or building up pressure – it reached an equilibrium with its surroundings. In a real thermal battery, stable pressure is important for safety and consistency, and here the simulation shows the PCM maintaining that stability after the initial settling period.

Total Energy vs Step

The total energy (potential + kinetic) of the system is practically flat after the initial few moments. In the beginning, there’s a tiny drop as the system stabilizes, but then the total energy line stays horizontal (no noticeable upward or downward trend). What it indicates: Energy conservation in the simulation. Because this was a closed system after initial setup, no energy was added or removed; the flat line confirms that the simulation obeys the conservation of energy – the energy in the system is constant. This is a good sign that the simulation ran correctly and that the PCM is simply redistributing energy internally (between kinetic and potential forms) rather than losing it. For example, if the PCM absorbed heat as latent energy, we’d see potential energy go up and kinetic energy (or temperature) slightly go down, but the total stays the same. The fact that total energy remains steady means all the energy is accounted for within the system. In a real thermal battery, this would be like ensuring that almost no heat is lost to the environment during the storage period – all the input energy is stored in the PCM, ready to be used later.

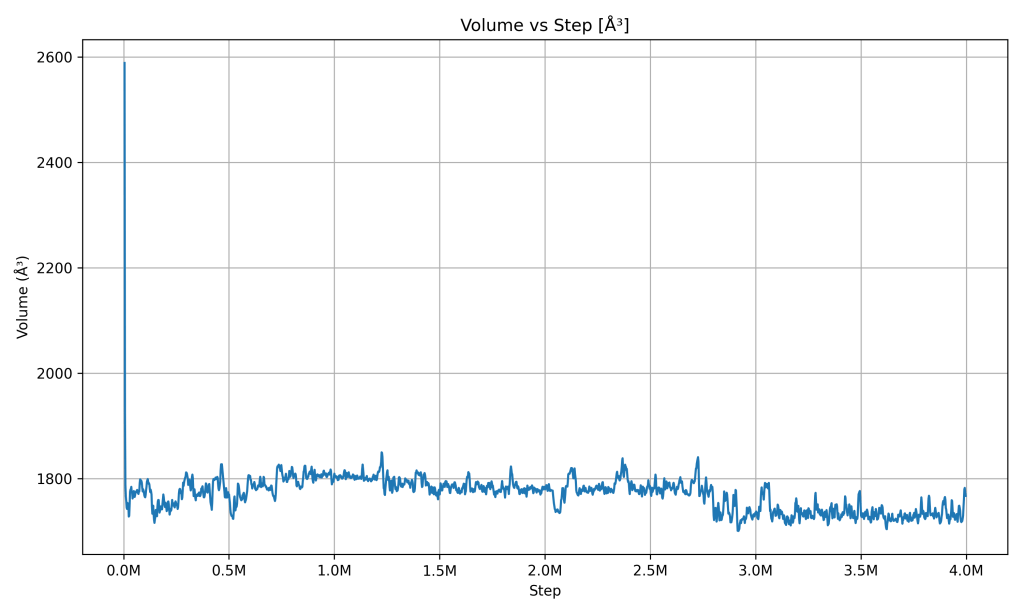

Volume vs Step

Volume vs Simulation Step. The volume of the simulated PCM (the size of the simulation box) changed noticeably at the start and then leveled off. The graph shows the volume dropping quickly in the early steps (meaning the material contracted or the simulation box shrank) and then fluctuating slightly around a stable value thereafter. What it indicates: The PCM adjusted its density and then reached a stable size. Early on, the large volume change likely came from the PCM sample finding a more compact, stable structure (for instance, if there were gaps or an expanded arrangement initially, the material pulled together once it equilibrated, which would reduce volume and increase pressure to normal levels). After that, the volume stayed roughly constant, showing that the material isn’t expanding or contracting anymore. This stability in volume goes hand-in-hand with stable pressure and temperature – all are balanced. In practical terms, a thermal battery material that doesn’t keep changing size once settled is important (to avoid stressing the container). The simulation indicates that after the PCM’s phase adjustment, its volume remains steady, meaning the system has structural stability at the operating temperature and pressure

Overall, the LAMMPS simulation shows that the PCM-based thermal battery system reached a stable equilibrium and behaved as expected for an efficient thermal storage material. The temperature and kinetic energy staying constant demonstrate thermal stability – the PCM can hold heat without large temperature swings. The constant total energy line confirms energy conservation – no energy was lost, meaning all the heat put into the system is stored. Meanwhile, the potential energy, pressure, and volume graphs indicate that the material settled into a steady state (finding a stable structure and size) after an initial adjustment. This is exactly what we want in a thermal battery: the PCM can absorb a lot of heat (high energy storage) while remaining stable and then release that heat when needed, all without damaging changes in the system.

These results underscore the benefits of using PCMs in thermal batteries. Because PCMs store heat as latent heat during phase changes, they can provide a high energy storage capacity and supply heat at a near-constant temperaturepubs.rsc.org. The simulation helps us visualize and confirm how the PCM performs internally – supporting what researchers have reported in the literature about PCMs being great for compact, efficient heat storage. By understanding the energy and stability profile of the PCM through this simulation, we gain valuable insight for designing real-world thermal batteries that are safe, efficient, and effective in sustainable energy systemspubs.rsc.org.